A Slowbrow Guide to the 60th Venice Biennale

PART TWO: ARSENALE, GIARDINI, AND SOME VERY STRONG CAMPARI.

3D-rendered faces. Abstract images and vignettes, projected onto a screen in a dark room with bean bags on the floor. Atmospheric, discordant sound that does more for the emotive power of the work than the work itself. Art about identity, where the concept begins - and ends - at writhing bodies and unflinching eye contact. Sound familiar?

If you’ve visited a contemporary art gallery or museum in the last 10 years, you’ve probably seen something like what I just described. I have never been someone who values hyperrealist painting over conceptual art, climate-controlled portraiture to audiovisual feasts.[1] But even I am tired of the sameness on display within the walls of contemporary art institutions around the world. Art and life are ouroboric, and so it isn’t surprising that a world which is increasingly obsessed with tech and abstraction produces art in the same vein[2]. After all, artists metabolise their environments. I myself write about digital cultures, AI and all the rest.

But although I understand that sometimes art can be a trojan horse[3], what I really long for aren’t candy shades that exists only on the CMY colour wheel, nor novelty VR/IRL hybrid experiences[4]. I know that digital processes require immense skill and creativity, too. But I get so much joy from seeing evidence of physical craft, artistic ability and delicious 3D materials. For a little while now, I’ve been quietly heralding the coming of a second-wave Arts and Crafts movement – from city people flocking to carpentry workshops to the resurgence of from-scratch cooking[5].

Adriano Pedrosa’s central pavilions at the Biennale have satisfied some of this appetite. Many of the works presented this year are borne of traditional materials and indigenous practices, whilst others stand up to a clout-driven art world through the sheer weight and human significance of the stories they tell. The selection below is a list of some of my personal favourites, in no particular order…

Do Not Agree with Agnes Martin All the Time, Evelyn Taocheng Wang (2022-2023), Giardini. This humorously titled series of works by Chinese/Dutch artist Taocheng Wang is a perfect display of quiet power. Aesthetically, her works are tender, delicate – reminiscent of schoolgirl doodles. But they force you to lean in and look closely at the magical, hyper-detailed miniatures on the canvas. Looking at them calms the mind.

Untitled, Maria Taniguchi (n.d.), Giardini. These monumental monochromatic canvases look deceptively simple from a distance. Upon closer inspection, signs of an incredibly labour-intensive and almost meditative process emerge. Taniguchi’s almost imperceptible mark-making in black on black is like a trick of the eye. Gotcha!

Personal Accounts, Gabrielle Goliath (2014-today), Giardini. An ongoing project documenting individual testimonies of patriarchal violence, this series of recordings shows BIPOC, queer, trans and indigenous people recounting their experiences. Goliath challenges the audience, forensically examining how we determine ‘believability’ and allocate our compassion when faced with such testimonies. The clips feature nothing but the moments in between words – paralinguistic elements like swallows, umms and breaths. It’s tender, disarming, and makes you really listen. An impressive feat to do so without words, in a world of audiovisual noise.

Le Fanciulle Laboriose, Giulia Andreani (2024), Giardini. This piece and its accompanying works in watercolour hit me in the gut. Andreani uses early 20th century archive photographs of women and girls at work and in education to inform her monochromatic paintings. They feel like ghostly monuments to an industrious generation of women, exuding repressed potential. They also remind me a little too much of portraits of my grandmother at domestic science school. I wonder where all of these women ended up?

Foreigners, Please Don’t Leave Us Alone With The Danes!, Superflex (2002), Giardini. Superflex’s bright orange graphic is unmistakeable. When I lived in Copenhagen, I used to see these bad boys all over the city and had no idea what they were. But, as I soon learned, this piece is more than just a stack of free posters to roll up and carry on to your Ryanair flight because it won’t fit in your luggage. It’s an ongoing public art project that pushes back against anti-immigrant rhetoric in Denmark. Superflex aren’t likely to stop printing them any time soon, I’m sure.

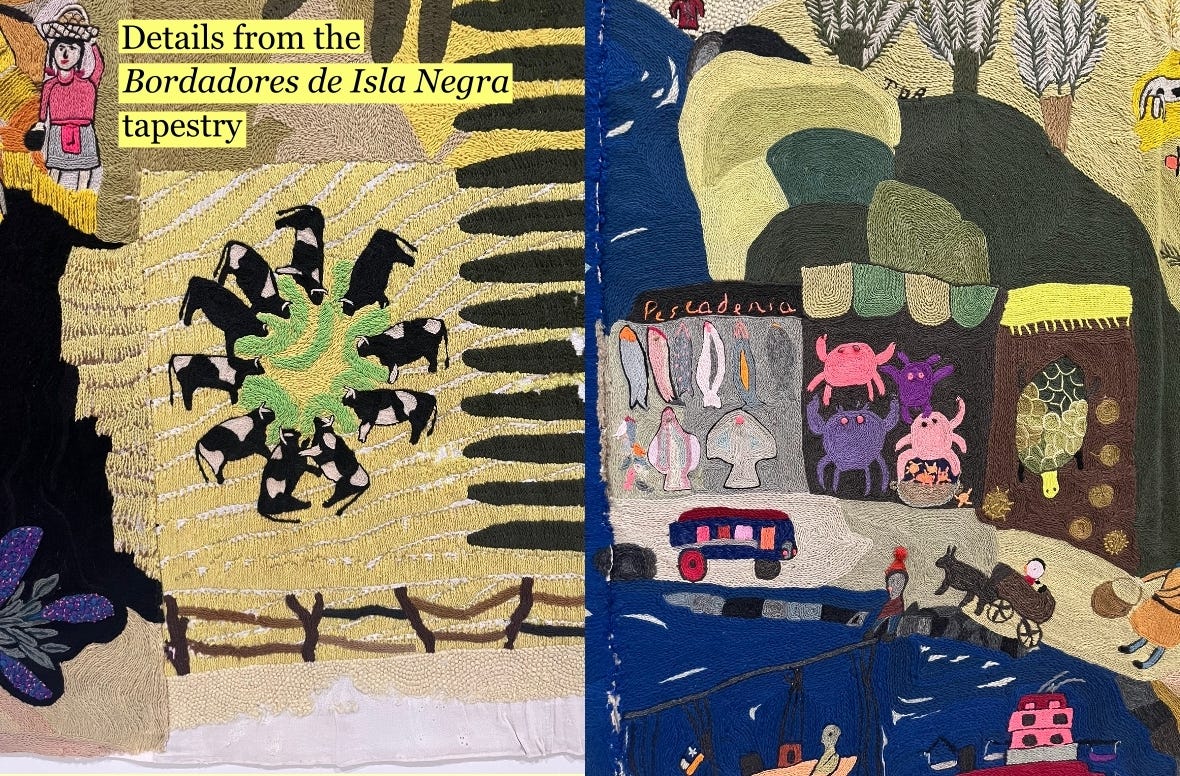

Bordadoras de Isla Negra (1972), Giardini. This is a piece dripping with history. The beautifully bright, 230x774cm large tapestry was hand-woven by a group of Chilean women in the early 70s and depicts daily life in Isla Negra, Chile. It disappeared in 1973, after the Pinochet dictatorship administration moved into the UNCTAD III[7] building that housed it. It ‘reappeared’ in 2019.

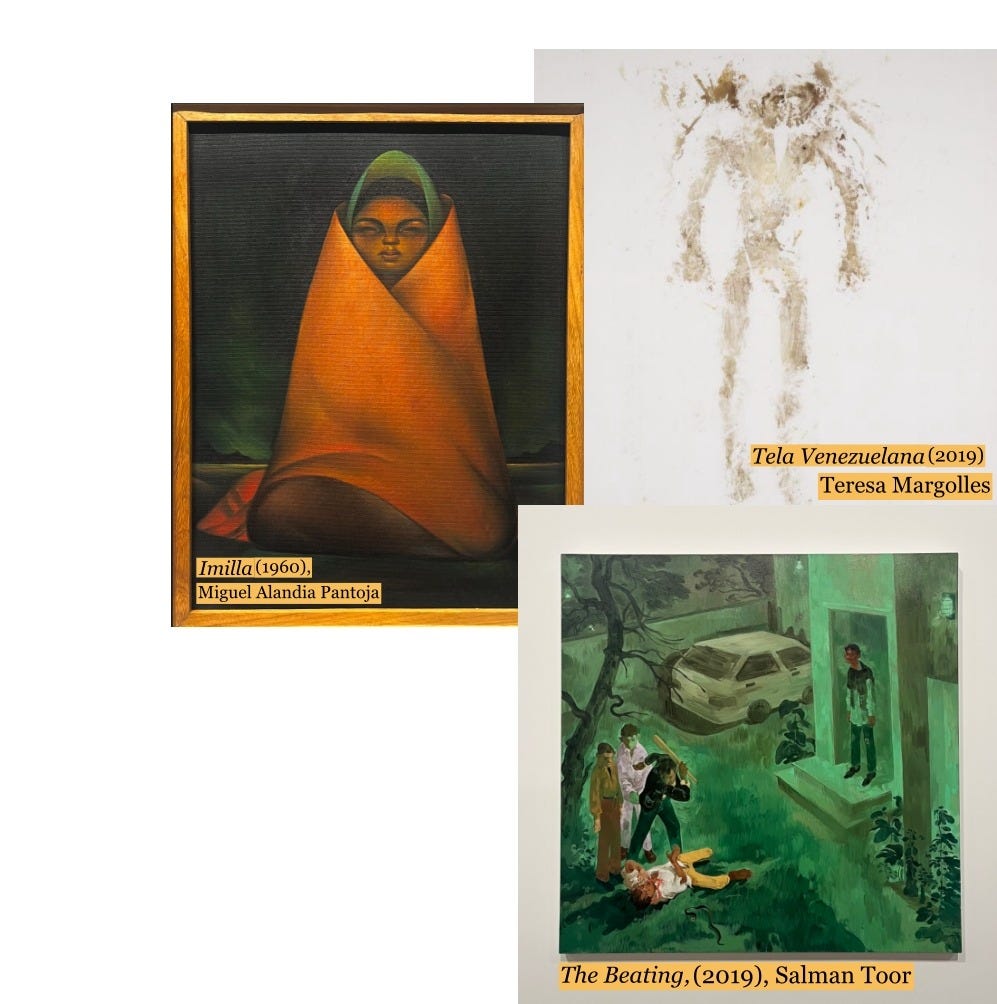

Imilla, Miguel Alandia Pantoja (1960), Giardini. This perfectly symmetrical portrait of a young girl by Bolivian artist Pantoja is almost Christlike. She is luminous, steadfast, wise beyond her years. We don’t know who or what she is standing sentry for in the dead of night, but know instinctively that it is something bigger than herself.

The Museum of the Old Colony, Pablo Delano (2022), Giardini. I mentioned this installation in Part 1 of my Venice guide. To reiterate: Delano’s examination of years of colonial rule over Puerto Rico is one of the most educational and confrontational pieces in the entire Biennale. It’s difficult to put into words, but in essence, he’s pulling down the USA’s pants. Delano shines a bright and unflinching light into a nasty corner of history that so many of us are not taught about… or taught to forget.

The Beating, Salman Toor (2019), Arsenale. I admire Toor’s vulnerability as much as his distinct artistic style. This piece is the harrowing conclusion to a series of beautiful, tender oil paintings, twilight-hued tableaus depicting gay life behind closed doors in the artist’s native Pakistan. There is no text in the guidebook to accompany The Beating. In a way, this mirrors the silence after a traumatic event. A leaving of the body, a muting of pain. The drooping figure in the doorway nearly broke my heart.

Tela Venezuelana, Teresa Margolles (2019), Arsenale. This piece really belongs in a history museum. It doesn’t belong on a market. Tela Venezuelana is an artefact of the violence of forced migration: the imprint of the dried blood of a young man who was shot down on the border between Colombia and Venezuela. Margolles collected this Turin Shroud during the young man’s autopsy, on scene at the Táchira River where he was killed.

being alone, Dean Sameshima (2020), Arsenale. This collection of clandestine photographs is a monument to loneliness and tentative self-expression. It also straddles a moral grey zone. Sameshima photographs men at the adult movie theatre, the backs of their heads, solitary silhouettes caught in moments of intimacy. But they are observers themselves. Where is the line between art and exploitation? What about consent?

El territorio de los abuelos, Rember Yahuarcani (2023), Arsenale. Bioluminescent figures dance through the space between the spirit and natural worlds. Half-bird, half-fish creatures swim upwards into clouds of brightly coloured atoms, descending like rays of light from the world above. This painting is a sumptuous panorama of the stories and worldview of the artist’s clan, the Aimeni of the Uitoto Nation of northern Amazonia. It is completely hypnotic. Yahuarcani has the imagination and talent of a more joyful Hieronymous Bosch, and makes me want to dive right into his world.

Warawar Wawa, River Claure (2019), Arsenale. Claure’s playfully constructed tableaus of his own community, the Aymara of the Andes, are part of a wider project that translates The Little Prince into a Bolivian context. Claure represents Aymara in a way that celebrates tradition and his native landscape, without obsessing about cultural ‘purity’. The colours are rich, the compositions mischievous and theatrical. A magical celebration of contradictions.

The works listed above are by no means an exhaustive representation of pieces I fell in love with during my visit. I also fell in love with the increasingly large Campari spritzes we were offered at Cantina Schiavoni by the Palazzo Gritti Badoer. But seriously: for more photos and a (slightly) extended list, please see my last Instagram.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to retire to my chambers. I’m editing this after a busy day of floral merchandising duties, with a tummy full of canned minestrone and sleepy eyes. Thanks for giving my words your attention – I know it’s a hot commodity.

NEXT TIME: THE PAVILIONS. EXPECT ALIENS BREATHING PERFUME, XRAY RECORDS AND ASBESTOS. SEE YOU THERE?

[1] I remember the sheer joy and awe I experience when visiting the Infinite Mix at 180 The Strand, on a school trip back in 2016. It was a cornucopia of audiovisual art, before the building that now houses Dazed Media, Charlotte Tilbury & Reference Point was refurbished.

[2] Like Ditte Ejlerskov’s The Cult of Oxytocin at Nikolaj Kunsthal in Copenhagen back in 2022. Every visitor walked away with an NFT. I was dazzled, but in the way that a toddler is dazzled by their first interaction with a smartphone. It gets old, fast.

[4] I also don’t want to have to read exhibition texts on my phone, as was the case at for Julie Mehretu’s last exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey.

[5] I like Nara Smith. Oops.

[7] Now home to the Gabriela Mistral Cultural Centre in central Santiago, the building was erected to host the Third session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 1972.